Empathetic Communication and the Conflicting Narratives of World War II and Holocaust History. Seminar in North Macedonia

Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia, was the location for the third meeting of the partners of the “Nonviolent Communication Approach in Adult Education in Historical Museums and Memorial Sites” project. The seminar provided an opportunity to further practise the “Nonviolent Communication” model in dealing with visitors, as well as to acquire in-depth knowledge about the complicated, historic and contemporary position of North Macedonia in the Balkan region and in Europe.

As part of the “Nonviolent Communication Approach” project, employees of four institutions – the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the Holocaust Memorial Centre for the Jews of Macedonia in Skopje, the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris and the Žanis Lipke Memorial in Riga – train in the principles of “Nonviolent Communication”. It is a communication model that serves to support dialogue and build societies based on empathy and understanding the needs of every person. The aim of the project is to use this model while working with the public and, through it, to activate groups of adult visitors in the field of expanding their knowledge about the Holocaust in Europe.

You can read more about this project here.

The Holocaust Memorial Centre for the Jews of Macedonia – the host of the training programme held in Skopje on 5th-7th September 2022, focussed on outlining the historical context for the wartime fate of Macedonian Jews, 98% of whom perished during the Holocaust. The second key issue was the manner in which Macedonian history influences contemporary international relations and conflicts of memory, including those about the Holocaust. These questions were introduced to the participants by a historian and associate of the Skopje museum, Professor Misho Dokmanovic, in the lecture entitled “When Past Determines the Future: History, Identity, Conflict and the Holocaust in North Macedonia” and by Professor Vasko Naumovski from the Ss. Cyryl and Methodius University of Skopje, a diplomat and politician who, in 2009-2010, while serving as the Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of North Macedonia, was responsible for the process of the country's integration into Europe.

To gain a better understanding of these issues, the participants learned, in detail, about the history of Macedonian Jews. Before the war, this community consisted of around 7,000 people, most of whom lived in three cities – Skopje, Bitola and Štip. In the spring of 1941, Bulgaria, an ally of the Third Reich, occupied central and eastern Macedonia. There, the new authorities introduced laws legitimising antisemitism and imposing numerous restrictions upon Jews. In March 1943, the Bulgarian authorities deported Macedonian Jews, along with Serbian and Greek Jews (over 11,000 people in total), to the German Nazi death centre in Treblinka, where they were all murdered. A handful of people, who managed to escape or had foreign citizenship, survived. Ten Macedonians, who helped the few fugitives, were honoured with the title of “Righteous Among the Nations”.

Macedonian-Bulgarian history and, to a large extent, also its wartime past, influences contemporary relations between these countries. Bulgaria does not acknowledge its occupation of Macedonia and its participation in the extermination of Macedonian Jews. The Bulgarian narrative emphasises the fact that the Bulgarian Jewish community was saved from death – in March 1943, at the request of forty-three parliamentarians, the deportation of 50,000 Jews to Treblinka was suspended. The role of Bulgaria in the wartime history of Macedonia is one of the contentious issues that a specially appointed Macedonian-Bulgarian historical commission is trying to resolve. The results of the commission's work are directly related to the process of opening EU accession talks with North Macedonia, currently being vetoed by Bulgaria.

During the visit to the permanent exhibition of the Holocaust Memorial Center for the Jews of Macedonia, these issues were discussed with its director Goran Sadikarijo. The modern exhibition, opened in 2019, is dedicated to the history of Macedonian Jews during the Holocaust, but is preceded by an extensive historical introduction, going as far back as 2,000 years. During the tour, particular attention was paid to the contents that are sometimes controversial from the perspective of the Bulgarian public, such as Bulgarian occupation, society’s indifference to deportation and artifacts related to it (including official documents, personal items and the door and window from the Monopol factory in Skopje, where Jews were imprisoned by the Bulgarian authorities). Bulgarian visitors sometimes object, show incomprehension or surprise when confronted with the history presented at the exhibition. Occasionally, they decline to visit the part about the war and the Holocaust. Conducting a dialogue in the face of strong emotions, resulting from differing knowledge about history, is a communication challenge which can be resolved by empathic communication – an attempt to refer to a common, basic need for truth, consistency or order and one's own emotions, such as sadness or anger.

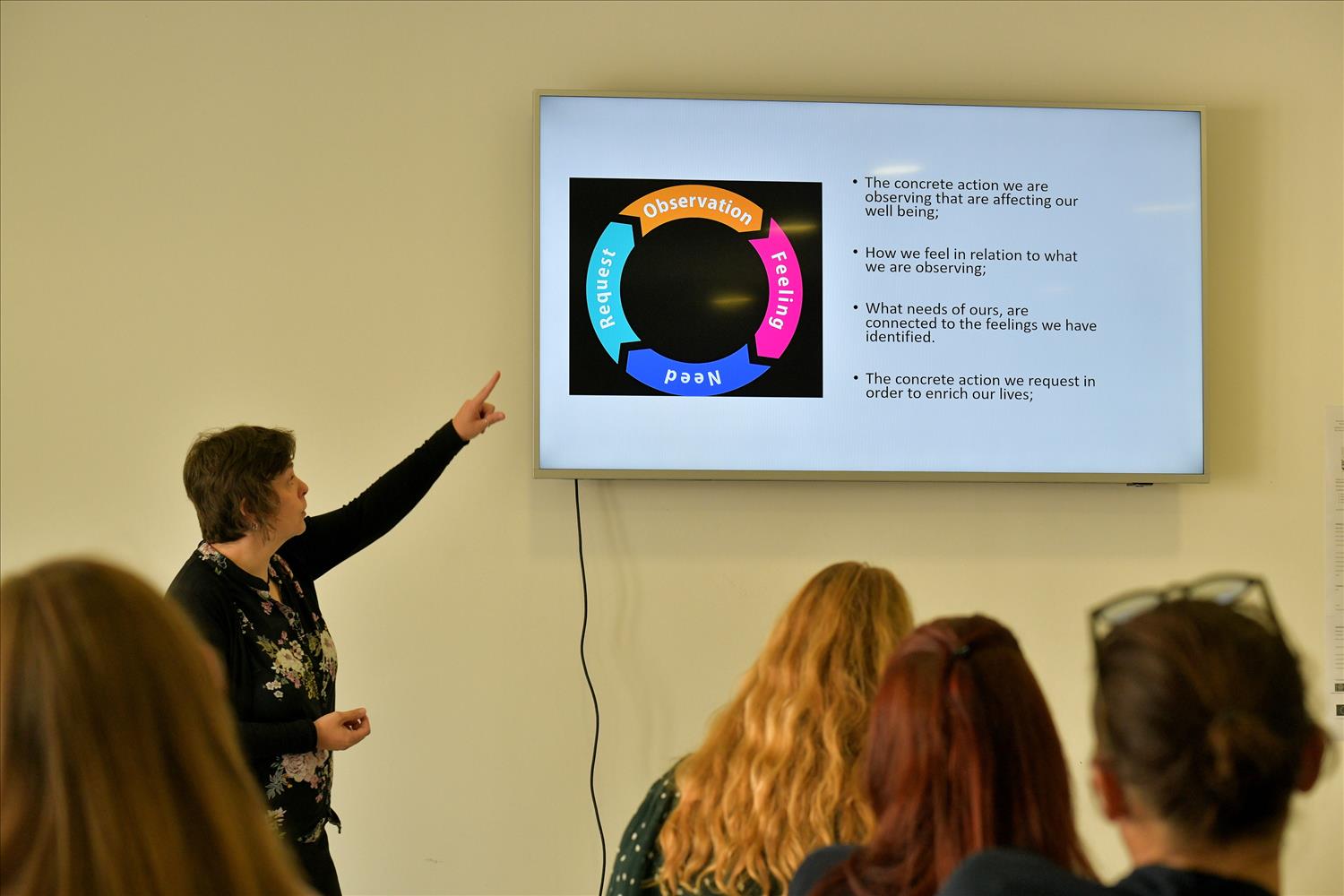

This and other examples of specific, difficult communication situations with the participation of visitors, in which empathetic communication could be used, were discussed during the training with Aleksandra Ristovski, a trainer of “Nonviolent Communication” and a Red Cross employee. Attention was paid to the needs and emotions behind particular behaviours of visitors, e.g., the need to be noticed and listened to – the possibilities and methods of responding to these needs were considered. An important area of discussions was about particularly difficult situations (e.g., involving an aggressive attitude), in which institutional regulations and security tools should also be applied. One of the seminar participants, Jacek Szczygieł, head of the security department at the POLIN Museum, provided advisory support regarding this.

During the training program, participants also visited places of remembrance relating to the history and the extermination of Macedonian Jews. In Skopje, they visited the premises of the Monopol tobacco factory where, in March 1943, before being deported to Treblinka, Macedonian Jews were held for several days in horrible conditions. There are two memorials on the premises of the factory – a plaque unveiled right after the war by the Jewish community and a monument, erected in 2004, by the current owner of the factory. Inside, in one of the rooms where people were imprisoned, it is planned to create a memorial site accessible to visitors. It is one of the few historical places in Skopje that has survived to this day. Most of the Jewish heritage was destroyed, along with much of the city, in the earthquake on 26th July 1963.

The participants learned about traces of the heritage of Macedonian Jews during a field trip of Bitola, a city in central Macedonia with one of the three main Jewish communities prior to the war. The group visited the oldest Jewish cemetery in the country, destroyed by the Bulgarian occupiers in the 1940s, the sites of synagogues, Jewish buildings and the former premises of Hashomer Ha’Tzair, as well as the monument commemorating Jews deported from Bitola, which was erected in 1958. Each year, the Macedonian Jewish community and representatives of the Macedonian government pay tribute to the victims of the Holocaust.

“The exchanges as well as the presentations were very rich, and allowed us to better understand some contemporary geopolitical and memorial issues, especially in the European context. The different NVC sessions and a tour organized on memory sites enlarged our perspective and the knowledge on the ways each institution has to deal with a national past or history,” says Delphine Barré, coordinator in Pedagogical Department of Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris.

The next training meeting is scheduled for spring 2023. The partners will meet at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw.

The Project is co-funded by the European Commission as part of the Erasmus+ ProgrammeThis publication was prepared with the financial support of the European Commission. It reflects only the views of its authors. The European Commission and the National Agency of the Erasmus+ Programme are not responsible for its substantive content.

Share: << Back

Any help from you is more than welcome.

Donate to continue with the successful work and education